UK Work & Study Immigration Statistics

In recent years, the United Kingdom has experienced dynamic shifts in immigration patterns, particularly among individuals entering for work and education purposes. These trends are influenced by a combination of domestic policy reforms, changing labor market demands, geopolitical relationships, and the UK’s appeal as a global education hub. This guide provides a comprehensive look at the latest data on work and study-related immigration to the UK and analyzes the implications for the country’s workforce, economy, and society.

Key Points

|

Long-Term Immigration at a Glance

June 2024, the UK recorded approximately 1.2 million long-term immigrants. The vast majority—nearly 86%—were non-EU nationals. This signals a major shift from pre-Brexit migration trends when EU nationals made up a large share of incoming migrants due to free movement rights.

Among non-EU immigrants, a significant proportion (82%) were of working age (16 to 64 years). This demographic distribution reflects the country’s reliance on economically active migrants to fill labor shortages, meet industry-specific demands, and support higher education institutions.

Work-Related Immigration: A Shifting Trend

Work-related immigration remains a critical component of the UK’s migration system. Between July 2023 and June 2024, over 286,000 work visas were issued to main applicants across various sectors. This figure, although slightly lower than the previous year, is more than twice the number issued in 2019, underscoring sustained demand for foreign labor despite increased regulatory scrutiny.

Key Observations

- Top Nationalities: Indian nationals received the most work visas, reflecting strong UK–India ties, especially in tech, healthcare, and engineering.

- Sector Trends: Tech and finance continue to attract skilled workers. Health and care saw high demand but experienced a 25% drop in visas due to stricter rules and ethical concerns.

- Dependants: Over 260,000 dependants were granted visas, mostly linked to care workers. This surge has driven recent immigration reforms.

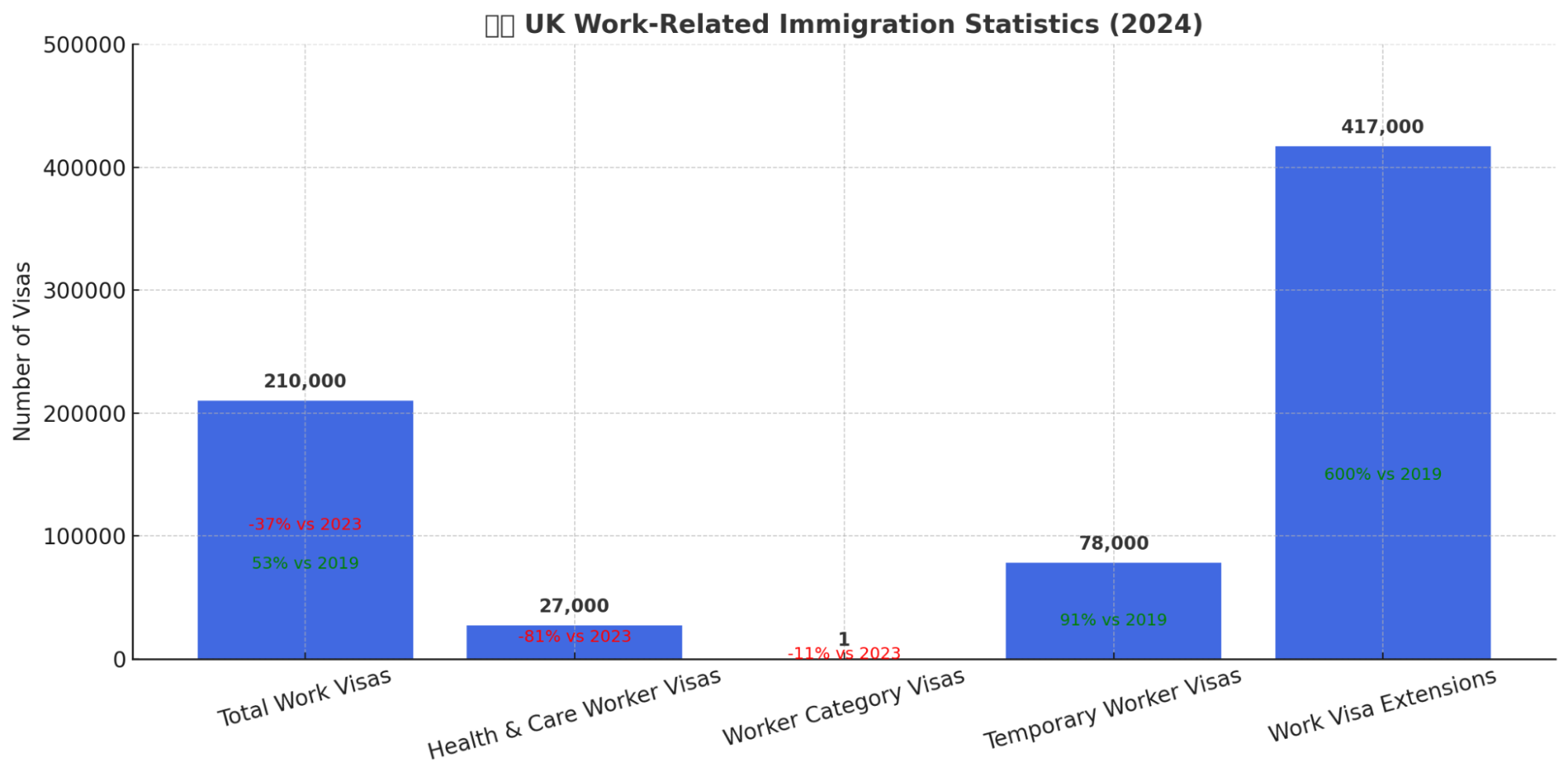

- Visa Numbers (2024):

- 210,000 work visas issued — 37% less than 2023 but 53% more than 2019.

- 27,000 Health and Care Worker visas — down 81% due to limits on dependants.

- Skilled Worker visas — fell by 11%.

- 78,000 Temporary Worker visas — up 91% from 2019, driven by agriculture demand.

- 417,000 visa extensions — nearly 7× 2019 levels, mainly via Graduate, Skilled Worker, and Care routes.

Study-Related Immigration: A Global Academic Destination

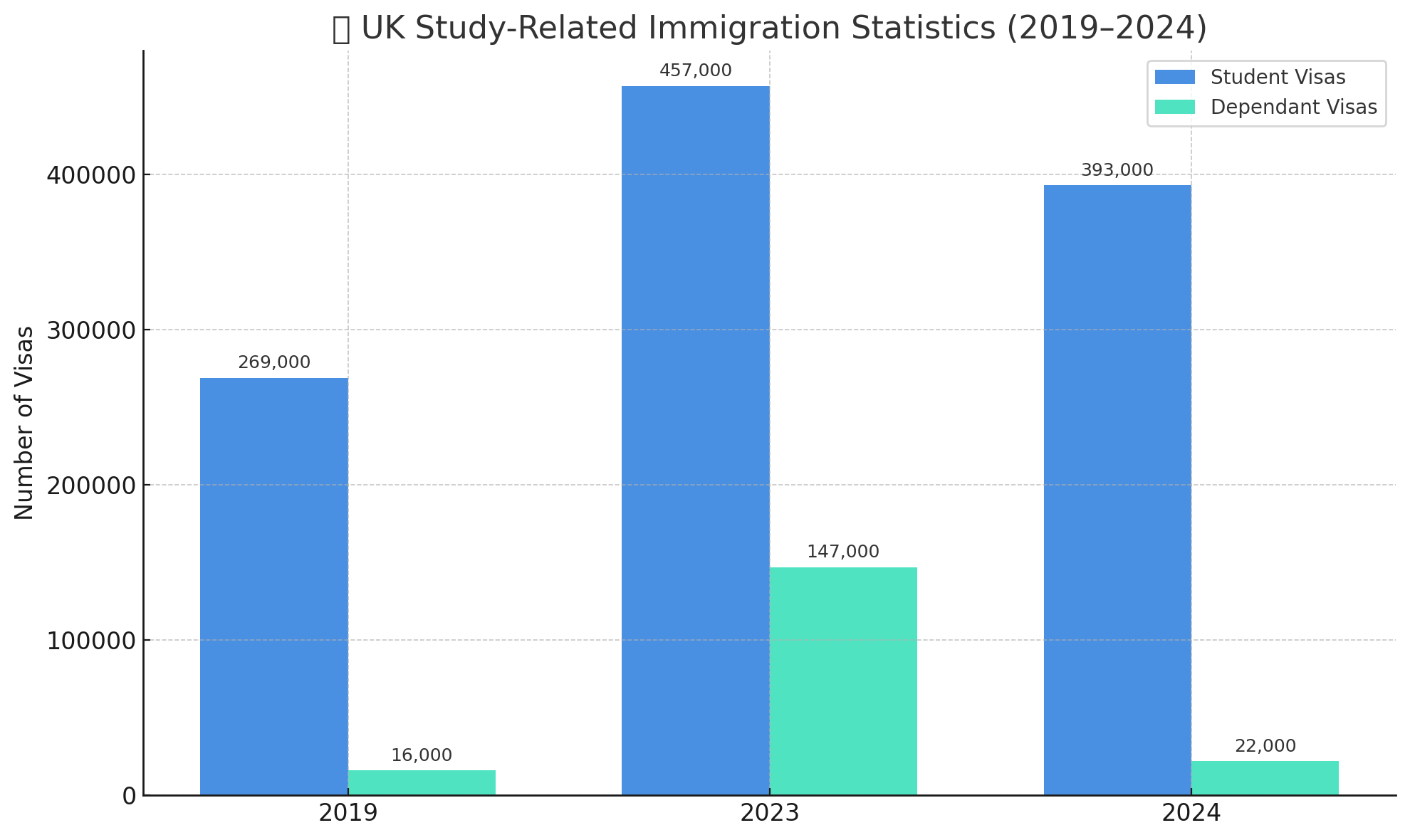

The UK has long been a preferred destination for international students. In the year ending June 2024, over 432,000 sponsored study visas were granted. Though this represented a slight decline from the previous year, the figure remains substantially higher than pre-pandemic levels and demonstrates continued global interest in UK education.

Key Insights

Level of Study: Around two-thirds of international students came to pursue master’s level qualifications, indicating the UK’s reputation for high-quality postgraduate education.

Top Source Countries: Among the top countries sending students were India, Nigeria, and China. Indian nationals in particular represented a significant portion, showing strong bilateral educational ties and student mobility.

Policy Impact: Starting January 2024, most international students were no longer permitted to bring dependants unless they were enrolled in postgraduate research programs. This policy change led to an 80% drop in dependant visas within the student visa category, significantly altering the demographics of student immigration.

Government Reforms and Their Impacts

The UK government has introduced several sweeping reforms aimed at curbing net migration. These changes came in response to record-high net migration figures, which peaked at over 900,000 in 2023. The reforms reflect political and public pressure to reduce immigration while still allowing the country to attract the talent it needs.

Major Reforms Include

- Longer Residency Requirements for Citizenship: The minimum period for migrants to qualify for British citizenship has been extended from five to ten years. This move is expected to reduce the number of people becoming permanent residents in the short term.

- Higher Salary Thresholds: Migrants applying for skilled worker visas must now meet a higher minimum salary requirement, making it harder for low-paying sectors like hospitality and social care to hire from overseas.

- Restrictions on Family Members: Both work and student visa holders face stricter rules on bringing dependants, especially if they are not in research or high-skilled roles.

- Healthcare Recruitment Limits: International recruitment for social care workers has been paused due to concerns over exploitation and to encourage domestic employment in the sector.

These reforms are expected to reduce net migration by at least 100,000 annually, although the long-term effects remain to be seen.

Trends in Integration and Workforce Contributions

Migrants coming to the UK for work and study contribute significantly to the national economy. In the labor market, they fill critical shortages in areas such as healthcare, construction, and technology. International students support the higher education sector not only through tuition fees but also by enriching campus diversity and contributing to the local economy.

However, integration challenges remain. Many sectors that rely heavily on migrant labor continue to report difficulties in hiring under the new rules. Additionally, changes to family reunification rights and settlement pathways may affect the UK’s attractiveness in a globally competitive talent market.

Conclusion: A Balancing Act

The UK’s current approach to work and study-related immigration reflects a balancing act between political pressures to curb overall numbers and the economic imperative to attract skilled workers and students. The data reveals that while immigration numbers remain high, especially for non-EU nationals, the government is actively reshaping the system to prioritize skilled, high-value migrants.

As new rules take effect, it remains to be seen whether the UK can maintain its status as a global magnet for talent while addressing domestic concerns about population growth and service pressures. What is clear is that work and study-related migration will continue to be central to the UK’s social and economic fabric in the years to come.

Steps to Secure Your eTA for the United Kingdom

- Step1: Complete the online application form by entering your passport details and required personal information.

- Step2: Make the payment securely online using a credit or debit card.

- Step3: Check your email for the payment confirmation and receive your eTA electronically.